One little pill

How national deworming programmes are changing the lives of children.

A simple and effective solution

Over 800 million children are at risk of infection from parasitic worms known as soil-transmitted helminths. These worms cause silent and widespread suffering.

But there is a simple and effective solution.

Treating children with medication – a single pill – has been shown to drastically reduce the number of worms in their bodies.

This pill – generously donated by global pharmaceutical companies – rids children of parasitic worms. After the worms are killed in the children’s bodies, they no longer prevent the absorption of key nutrients, or compromise health and cognition in the millions of children receiving treatment.

Tremendous progress

Since 2012, CIFF – working with a range of partners and governments on the ground – has been supporting endemic countries to develop and run deworming programmes, striving to reach the WHO target of treating at least 75% of all at-risk children in endemic countries by 2020 and bringing the prevalence of heavy-to-moderate infections down to less than 1%.

CIFF is supporting programmes in three heavily-affected countries – India, Ethiopia and Kenya – which treated nearly 110 million children in 2015 alone (more than double the number that were treated in 2014).

Below is a quick overview of these three programmes and the impact we are starting to see.

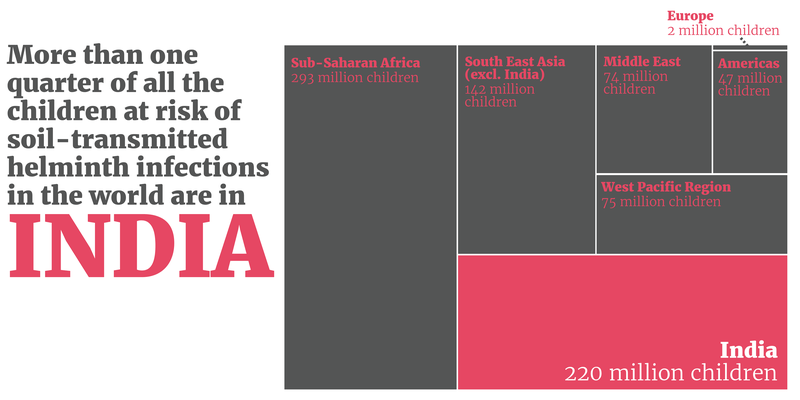

India has the greatest number of children at-risk of soil-transmitted helminth infections in the world – more than 220 million. India alone accounts for over one quarter of the world’s infected children.

Scaling up deworming efforts to treat these children in India is essential to reaching the global WHO target.

Identifying children at risk

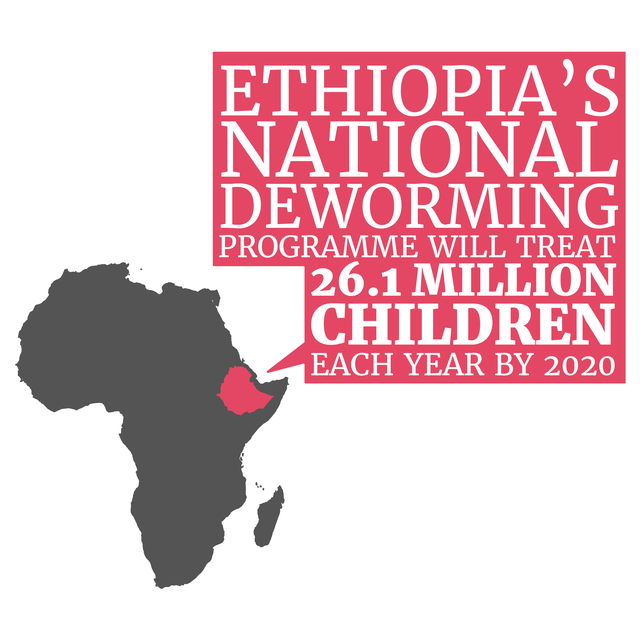

In Ethiopia, both soil-transmitted helminth infections and schistosomiasis (a worm infection acquired through contact with water) are prevalent in children and adults.

The Ethiopian Public Health Institute surveyed the country to determine areas where deworming is needed. The data shows that 29.6 million children (6.5 million of them pre-schoolers) are at risk of infection in the country.

In order to reach these children, CIFF is supporting the Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health and the Ethiopian Public Health Institute to run and evaluate a national deworming programme. Technical support is being provided by the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative and Evidence Action.

An estimated 17 million children were targeted for treatment in November 2015 with another round planned for April 2016.

Surpassing targets & treating children

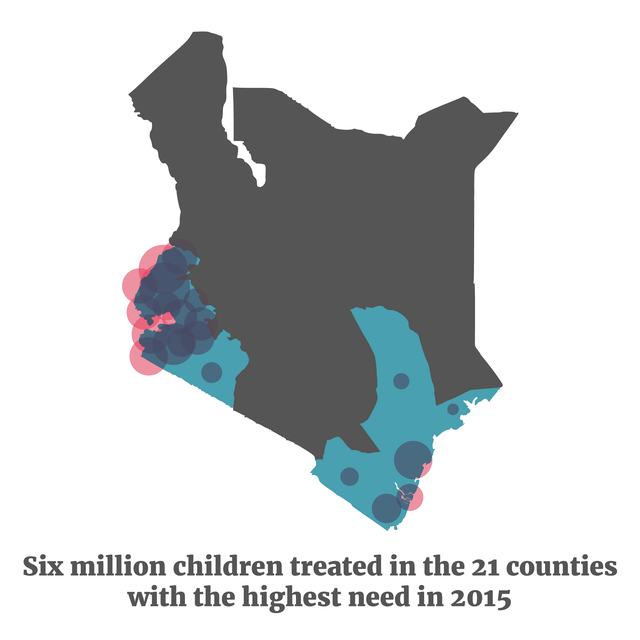

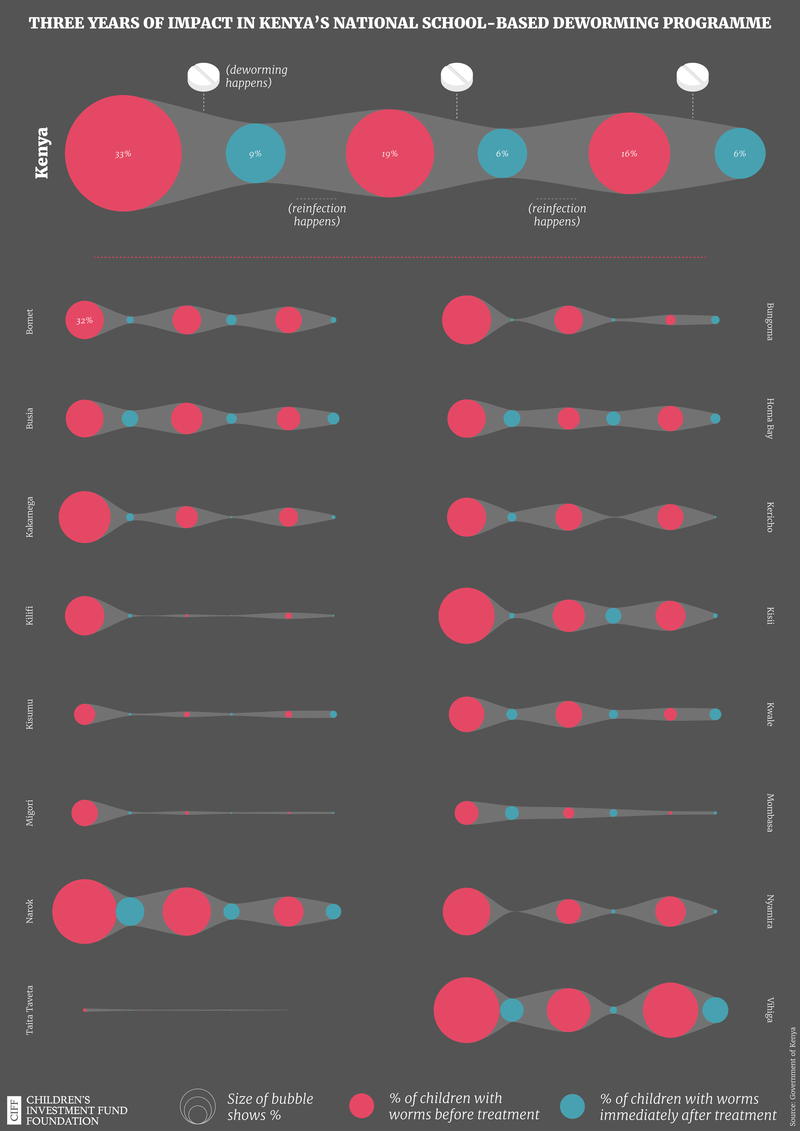

Kenya has seen great success both in treating children and seeing reductions in infection prevalence.

Figures for the first three years of implementation show that the programme has surpassed its target every year.

With technical support from the Deworm the World Initiative at Evidence Action, teachers handed out deworming medicine to more than six million children each year in 2014 and 2015.

Using data & evidence

A critical factor behind the success of Kenya’s deworming programme has been the use of scientific evidence to target treatment and monitoring data to manage the programme.

Prior to roll out of the programme, the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) conducted mapping to determine the need for deworming treatment across the country. This enabled the concentration of resources where they were needed most and allowed the government to provide treatment for all at-risk children.

It is too early to measure impact in Ethiopia or CIFF-funded states in India, but KEMRI has been collecting data on prevalence (percentage of children with worms) and intensity (percentage of children with moderate-to-heavy infections) for the last three years. You can download KEMRI’s reports on our grant page.

The infographic below shows the change in prevalence rates – both before and immediately after treatments – over the three years of Kenya’s National School-Based Deworming Programme, broken down by counties. A PDF of the infographic can be downloaded here.

This continuous re-infection between deworming rounds shows why it is essential to embed the programme in government systems and continue rounds of deworming, while monitoring the impact.

During each round of deworming, teachers are trained and held responsible for recording the number of treated enrolled and non-enrolled children, including those aged five and under. This data is sent back to the county and national level, where it is reviewed by both ministries to improve programme quality. The Kenyan Government also uses this monitoring data to determine and manage the performance contracts of government officials.

We know that deworming medicine has a positive effect on the children thanks to the Kenya Medical Research Institute. However, the data also shows that worms tend to re-infect quickly, so, unless treatment is repeated systematically and according to the guidelines, intestinal worms will return to their original levels very quickly, eradicating any past gain.

Researchers are working on models that indicate it might be possible to stop the reinfection cycle, even if sanitation and economic development remain poor. We are funding this kind of innovative research – through the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative and the Neglected Tropical Diseases Modelling Consortium – to understand what the best strategy for this would look like.

Photo: Child receiving treatment for worm infection on India’s 2016 National Deworming Day